Regulatory Leadership for a Culture of Quality in the Medical Device Industry

This article discusses governance and implementation infrastructure as critical factors in cultivating a culture of quality and building the necessary trust employees may need to help achieve it. The author outlines the critical attributes of a culture of quality, explains how such a culture can be built, the benefits it offers and touches on the roles played by regulatory/quality professionals in leading the effort to build quality.

The Case for Quality

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in partnership with the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC), launched the “Case for Quality Initiative.” This initiative sought to shift the mindset of the medical device manufacturer from mere regulatory compliance to true product quality. (1)

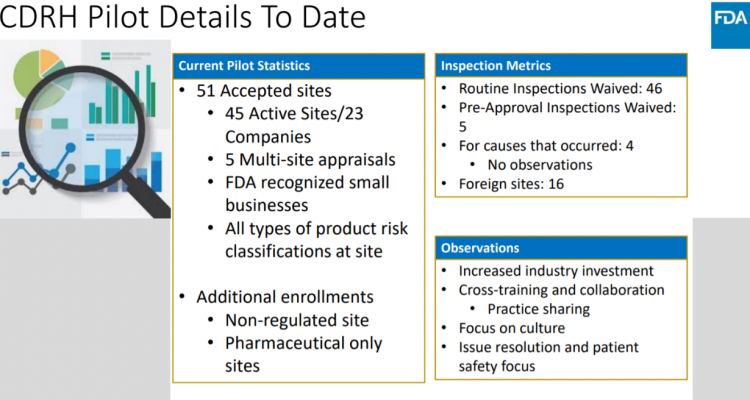

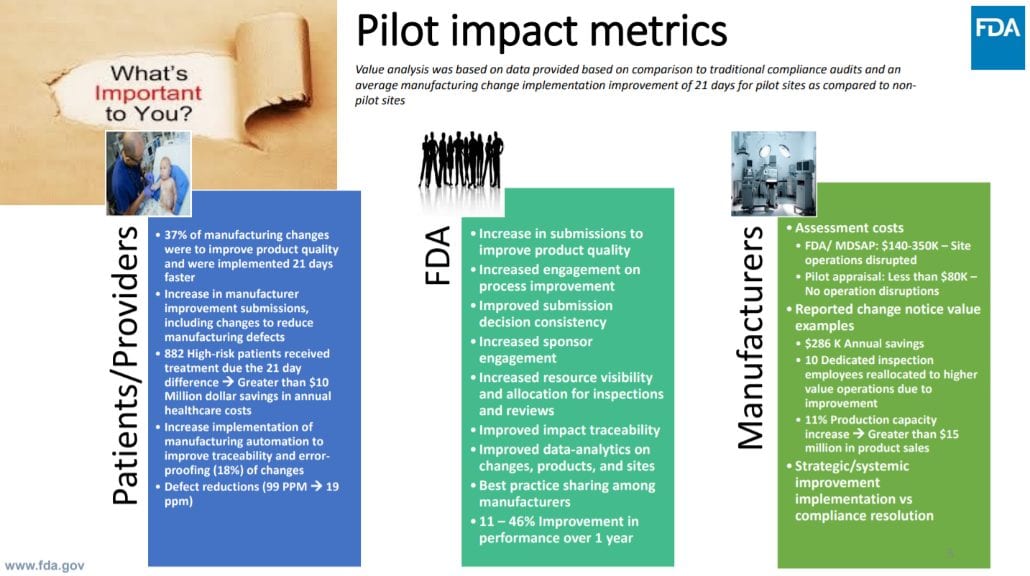

True product quality dismisses the notion that quality activities are just “boxes” to check but, rather, focuses on continuous improvement of processes to consistently yield safe and effective products. To demonstrate how an increased focus on true quality can benefit all stakeholders, including industry, patients, payers, providers and others, in 2018, the FDA invited medical device manufacturers to participate in a voluntary pilot program. As part of the program, participants agreed to an appraisal of their organizational practices and committed themselves to further innovate their quality practices. In return, the participants experienced streamlined engagements with FDA and reduced surveillance and inspections (Figure 1). (2)

The appraisal was conducted by a certified, third-party against an adapted Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) model. The CMMI appraisal model used for this pilot focused on 11 practice areas which, together, provide a holistic view of an organization’s approach to true quality (Table 1).

In September 2019, FDA released a report detailing the successes of the pilot program with the recommendation that the pilot be converted into a fully operational program for the US medical device industry. (3) Notable achievements, such as an 11 percent increase in production capacity, a 21-day reduction in change implementation and a reduction in defects were observed across pilot participants (Figure 2). (4)

It is well known that, along with benefits, maturity and capability appraisal models have inherent cross-cultural, cross-industrial limitations which prevents any “one-size-fits-all” solution even within the same region. (5) Nevertheless, trends reported through FDA’s pilot program provide key insights into the operational practices of US medical device manufacturers. Across the board, pilot program participants reported an increase in the governance and implementation integration practice areas. Together, these practice areas describe the actions necessary to build a culture of continuous improvement or a “culture of quality.” Pilot participants realized that success in the other nine practice areas would not be possible without a culture supporting and working to achieve true quality.

Table 1. CMMI Development Model Version 2.0 Appraisal Practice Areas for FDA’s Case for Quality Voluntary Pilot Program

| Practice Area | Description |

|---|---|

| Configuration Management | Manage the integrity of work products using configuration identification, version control, change control and audits. |

| Estimating | Estimate the size, effort, duration and cost of the work and resources needed to develop, acquire or deliver the solution. |

| Governance | Provides guidance to senior management on their role in the sponsorship and governance of process activities. |

| Implementation Infrastructure | Ensure the processes important to an organization are persistently and habitually used and improved. |

| Managing Performance and Measurement | Manage performance using measurement and analysis to achieve business goals. |

| Monitor and Control | Provide an understanding of the project progress so appropriate corrective actions can be taken when performance deviates significantly from plans. |

| Planning | Develop plans to describe what is needed to accomplish the work within the standards and constraints of the organization. |

| Process Quality Assurance | Verify and enable improvement of the quality of the performed processes and resulting work products. |

| Product Integration | Integrate and deliver the solution that addresses functionality and quality requirements. |

| Requirements Development and Management | Elicit requirements, ensure common by stakeholders and align requirements, plans and work products. |

| Technical Solution | Design and build solutions that meet customer requirements. |

What is a Culture of Quality?

There are many definitions of a “culture of quality” and what such a culture might look like across various industries. Harvard Business Review defines a culture of quality as “an environment in which employees not only follow quality guidelines, but also consistently see others taking quality-focused actions, hear others talking about quality, and feel quality all around them.” (6) The American Society for Quality (ASQ), in collaboration with Forbes in 2014, contrasts that definition with a description of an organization lacking such a culture, as one in which someone “put some procedures in place and then, once a year, just before their audit, they clean up the factory.” (7) A true culture of quality has a strong foundation of compliance to notable industry standards, such as ISO 9000 or ISO 13485. However, a culture of quality is much more than simply demonstrating compliant processes. A culture of quality exists when employees understand the value of a process and work together to continually improve the process. It is the regulatory/quality professional’s responsibility to encourage a creative process of improvements from employees while maintaining a strong foundation for compliance.

Process, Tools, and Trust

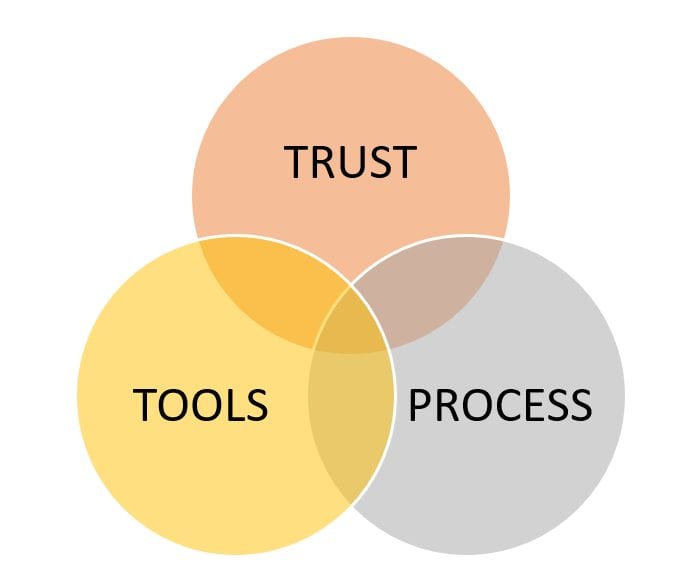

An organization’s quality management system is comprised of a set of processes and the tools to execute those processes. Processes and tools are constantly being created, instated, updated, made obsolete and then replaced, which is the very definition of “continuous improvement.” However, a system in constant flux can be thought to be disruptive to users (the employees). Changes and improvements also can be perceived as imposing, restricting or fleeting with little-to-no value and, therefore, unlikely to be executed. Such a perception would undermine any progress made toward building a culture of quality. For continuous improvements to be welcomed, employees must trust how these process or tool improvements will allow them to better deliver safe, reliable and effective products without undue burden on employees. It is the role of the organization’s regulatory/quality professional to provide the framework (processes and tools) employees trust so they can produce high quality products and services (Figure 3).

What is trust? Trust can be defined as “a consistent experience of competence, integrity, honesty, transparency, commitment, purpose and familiarity.” (8) Users of a process may not need or have the capacity to understand the many details of “why” something is done in a particular way. But when they trust the process, there is greater peace-of-mind for the process resulting in a product of the highest quality. Users experience a reduced cognitive load since they are confident nothing is being missed. However, even in this definition of “trust” the juxtaposition of consistency and continuous improvement presents a challenge for the regulatory/quality professional. While the rate of change in the field of medical device regulation tries to catch up to the rate of technology advancement, the regulatory professional must work to maintain a stable and credible continuous improvement process through a well-defined governance and implementation infrastructure.

The Role of Governance

Cultivating a culture of quality begins with a vision from executive leadership, but can only succeed with a unified, visible front championing the vision at all management levels. A quality culture with a strong governance clearly establishes the role and responsibility for management positions to both champion and enforce the culture of quality in the organization. Employees need to see that management prioritizes quality and safety, not only in words, but also in action. Actions following through on words builds trust. Examples where management can actively champion a culture of quality include:

- Encouraging the identification of quality issues by team members

- Being the first to dismiss any attempts of blame, shame or fault

- Sharing accountability of a quality issue in the case of a product failure in the field

- Openly and sincerely thanking and appreciating a team member for identifying a quality issue prior to release of a product

- Giving the project team adequate time and budget to fully develop quality plans and other quality documentation

- Ensuring the project team spends adequate time to develop quality plans and other quality documentation

While championing the culture of quality can be uplifting, the “flipside” of governance or enforcement is not regarded as something positive. Furthermore, it is typically the responsibility of the regulatory/quality professional to do the enforcing in the form of design reviews and Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPAs). When a quality issue arises or a potential issue looms on the horizon, it helps to approach the issue from a culture of quality perspective. Can the root cause of the issue be attributed to a failure in process, tools or trust? The regulatory/quality professional should first seek to understand motivations behind actions leading to the quality issue. Did a tool fail without the proper indicators? Did the process not clarify the value or purpose of the indicator? Did the user not trust the indicator and move ahead regardless? Whatever the root cause, users of the process should be involved in the improvement effort. Engagement in the process, especially with changes in process, builds trust.

Implementation and Infrastructure

The notion of ‘disruptive change’ is exciting when it comes from a tech startup promising to revolutionize an industry with its new widget. In the world of medical device development and manufacturing, disruptive change threatens inconsistencies, unknowns and headaches for regulatory/quality professionals. The continuous improvement that supports a culture of quality has the potential to be disruptive without a proven implementation infrastructure. As the name implies, implementation infrastructure defines a consistent, stable and validated method for developing, testing, initiating, monitoring and improving process changes. Such infrastructure also must ensure that senior personnel will support, sponsor and enforce the process changes. An example of a mature implementation infrastructure may look like the following:

- Results of an internal audit or CAPA provides evidence-based rationale for a process change.

- The process change has objective criteria for improvement and has the potential to make a subtle yet impactful change (based on a metric or threshold).

- All employees or potentially effected groups are notified of an upcoming process change and are given opportunities to provide feedback.

- The process change is rolled out to low risk yet qualified production groups to verify effect on performance and to get workflow feedback. Senior personnel train selected production groups prior to verification and closely monitor these groups.

- If the change passes verification, it is then “rolled out” to all groups for implementation.

- Over a pre-determined time period, the process will be closely monitored and validated against the objective criteria for improvement.

- After the process change validation is complete, the process is still monitored as necessary and the cycle of improvement begins again.

- A continuous stream of planned improvements can achieve a level of consistency with a regular update schedule, like those of software update releases

The Case for Quality From a Business Perspective: Conclusion

The case for quality from a business perspective has been clearly defined and demonstrated for years. (9,10) Key drivers behind such investment include quality’s positive impact on effectiveness and profitability, quality’s ability to serve as a key competitive differentiator and the view that high quality represents a barrier to entry to competitors. Quality is also viewed as a vital tool in risk management and the drive for innovation. (11) To sustain return on investment, the organization needs to cultivate a culture of quality by continuously improving the organization’s processes, tools and sense of trust in those processes and tools. The practice areas of governance and implementation infrastructure highlighted by the CMMI Maturity Model are critical factors in cultivating a culture of quality and building trust. The paradigm shift from compliance to true quality starts from the top and flows to each of the organization’s members, no matter their role or position.

Regulatory/quality professionals are responsible for the organization’s quality processes and tools. They should constantly question whether the processes and tools make sense regarding what the organization values and what the organization is trying to achieve. Regulatory/quality professionals should work to streamline processes, not with the goal of achieving compliance, but by reducing cognitive load on the users of the process so that they can make quality-driven decisions. They should be the collaborative partners in the improvement process, engaging process users to determine the least burdensome approach to solve quality issues and create value from a process. At the end of the day, the results of true quality should benefit patients and the organization, not the auditor.

References

- Case for Quality. FDA website. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/quality-and-compliance-medical-devices/case-quality. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Vicenty C. “The FDA’s Case for Quality: Voluntary Pilot Program Update.” 20 June 2019. Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). https://mdic.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CDRH-update.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Case for Quality. Voluntary Manufacturing and Product Quality Pilot Program Results. Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) website. https://mdic.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Case-for-Quality-Pilot-Report.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Op cit 2.

- Biró M, Messnarz R and Davison A G. “The Impact of National Cultural Factors on the Effectiveness of Process Improvement Methods: the Third Dimension.” Software Quality Professional. American Society for Quality (ASQ). Volume 4, Issue 4. September 2002. pp.34-41. http://www.asq.org/pub/sqp/past/vol4_issue4/biro.html. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Srinivasan A and Kurey B. “Creating a Culture of Quality.” Harvard Business Review. April 2014. https://hbr.org/2014/04/creating-a-culture-of-quality. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Culture of Quality. Accelerating Growth and Performance in the Enterprise. Forbes Insights. https://images.forbes.com/forbesinsights/StudyPDFs/ASQ_CultureofQuality_REPORT.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Felton J. “Building Trust: a Leadership Imperative.” Lead Change website. June 2019. https://leadchangegroup.com/building-trust-a-leadership-imperative/. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Cokins G. “Economic Case for Quality. Measuring the Cost of Quality for Management.” Quality Progress. September 2006. American Society for Quality (ASQ). https://www.hmg.com.au/ayb/COQ.pdf. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Cost, Quality and Cost of Quality. Quality Magazine. February 2018. https://www.qualitymag.com/articles/94524-cost-quality-and-cost-of-quality. Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Op cit 6.

About the Author

Amaris Ajamil, PhD, RAC is the senior quality assurance and regulatory affairs engineer at Simbex, a medical device and consumer health product development company. Her quality assurance and regulatory affairs team provides compliance and quality product development oversight including regulatory strategy, usability, risk analysis, verification and validation activities, auditing and continuous process improvements. Ajamil is a strong believer in user-centric design for delivering safe and effective therapies. She holds a doctorate in biomedical engineering from the University of Miami. She can be contacted at aajamil@simbex.com.

Cite as: Ajamil A. “Regulatory Leadership for a Culture of Quality in the US Medical Device Industry.” Regulatory Focus. January 2020. Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society.

Originally published via Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society (RAPS)